Colonial legacies and identities of the GERD conflict

In the last posts, I mentioned that the specific geography of the Basin is one of the main reasons for the difficulty of solving the conflict between Ethiopia and Egypt. However, I want to suggest something other than an environmentally deterministic conclusion that ignores social factors. In reality, the potential solution benefits of sharing and cooperation are hindered by the region's historical (colonial) legacies. When I asked locals' opinions about GERD during my time in Ethiopia, everyone was enthusiastic and satisfied with the project. They claimed it would 'compensate for the injustices of the past and bring a bright future to all Ethiopians'. This idea of injustice and strike back to Egypt appears in the following video (from 3:50). Ethoiphian leaders want to set the rules after the country's historical marginalisation on managing the water of the Nile. Simultaneously, as the identity of Egypt is intertwined with the river, any measures or modification on water flow is unacceptable to them. Over history, Egyptians and Westerners created a discourse that suggests the country is the ruler over the river by calling it 'the gift of the Nile'. Therefore, claiming their historical rights over the river within the conflict further increases the tension with the downstream country as Ethiopians think these are a colonial heritage.

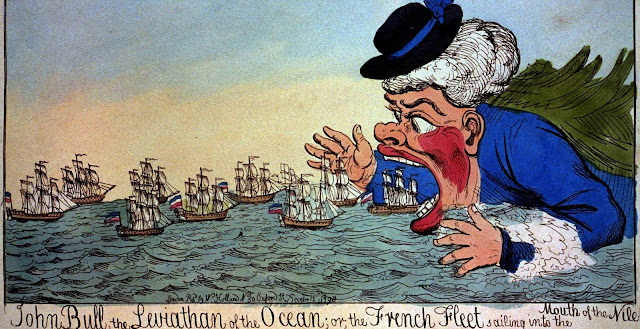

In the age of Imperialism, as one of the only sovereign African countries at that time, colonisers, especially Britain, were not considered Ethiophian's equal partners. At the beginning of the 20th century, treaties over the Nile only supported the interest of Egypt and Britain. In 1902 the first of these made them the exclusive user of the river. The treaty stated that Ethiopia could not build anything that affected the flow of the Blue Nile without Britain's consultation and permission. While the same year, Egypt finished the Aswan dam construction, impacting the up and downstream environment since then. The next milestone was in 1929 after the upstream country gained partial independence from the Empire and their rights over the Basin. Supported by the Britsh, Egypt could veto every Nile Basin construction and supervise the whole river after the treaty. Colonial frameworks remained and even strengthened in1959 when Egypt 'earned' 66% of river flow, giving the remaining proportion to Sudan and evaporation. The less developed Ethiopia and other riparian states were neglected entirely by the consultations and the signing.

So, for Ethiopia, the construction of the dam, besides its economic advantages from power generation, is about resisting Egypt's hegemony and gaining 'environmental justice' after the colonial treaties. Egypt's stance that water is theirs by law will not lead to cooperation between the sides. However, ironically Ehtiophia's attitude that prioritises individual utilisation perpetuates the same colonial legacy that the country despised in history. Therefore, it is clear that both parties need to change their cooperation tactics if they want to solve the crisis and distribute the water more fairly.

The remaining colonial legacies are only a part of cooperation boundaries. In the next week, I will look into another one: the discourse suggesting that dams will bring a better future for all Ethiopians.

Interesting historical perspective that helps the reader better understand the origin of the mentioned conflict! I wonder what would be the most fair compromise for both Ethiopia and Egypt to find common ground, while taking into account the past conflicts for the best outcome.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment! In later posts, I dealt with this question, but to sum up, I think, most importantly, Egypt needs to accept the hegemony shift in the basin. Simultaneously, Ethiopia must promise that in the case of dry years, it will provide an extra water supply for the downstream countries.

ReplyDelete